Departures and arrivals at major airports aren’t as simple as lining up with the runway and climbing up to cruising altitude. Aircraft at most major airports follow SIDs and STARs, which give aircraft a set guide for departing and arriving. SID stands for Standard Instrument Departure. STAR stands for Standard Terminal Arrival. These are the primary way aircraft route out of and into airports, at least at major ones. So let’s take a look at how they work, and what the pilots do in order to follow these.

How do they work?

Airports sit in their own terminal area – a sort of protected airspace around (and above) the airport. Beyond this you have other sorts of airspace, generally controlled and filled with things like airways and a lot of traffic. So when designing departures and arrivals, consideration of the other airspace, where traffic is coming and going from, terrain, and even things like noise sensitive spots have to be taken into account.

SIDs and STARs are therefore designed with all this in mind, to ensure traffic routes around in a nice, safe, orderly fashion to and from the airport. But there isn’t usually just one way in and one way out. That would be inefficient, because of course aircraft all tend to be heading off to different destinations. So these procedures are designed with the direction of routing in mind too.

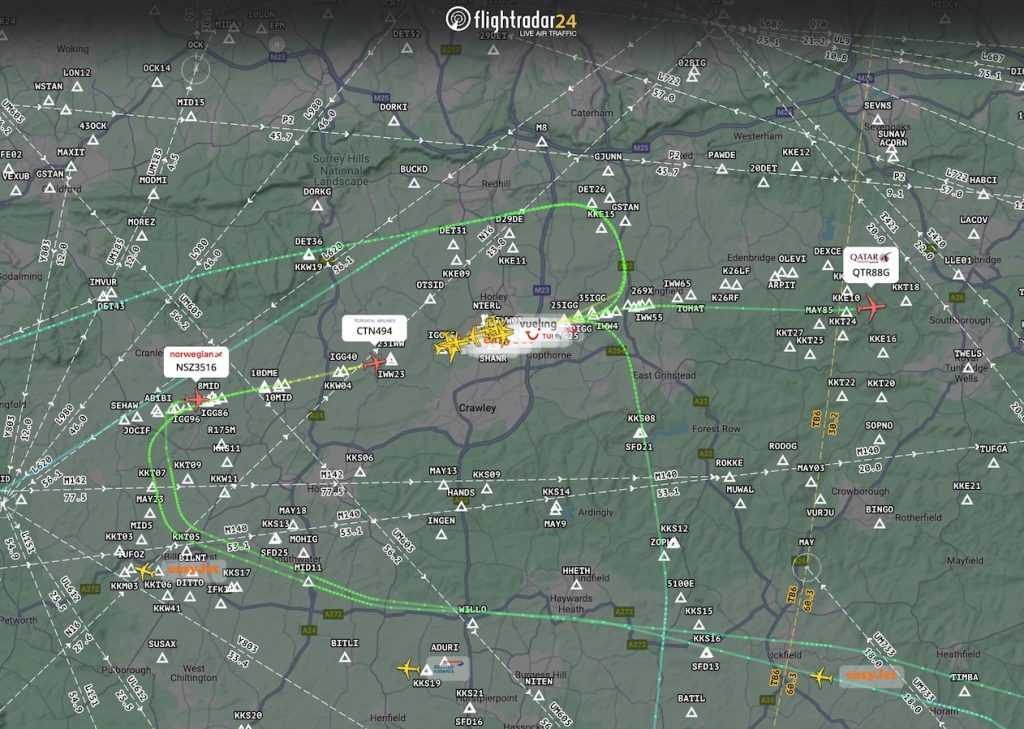

Take for example EGKK/London Gatwick airport. Aircraft taking off from the westerly runway and heading west towards the USA might fly a NOVMA 1X departure. This will connect them to the first airway routing them west. But aircraft who want to head south will probably fly a BOGNA 1X. There are actually 26 different SID plates for Gatwick, so a lot of different ways to leave from there.

Each of the SIDs has to consider all the things we mentioned above – terrain, other traffic (coming from other airports), noise sensitive spots etc. So in addition to the waypoints that set the routing, they also tend to have altitude and speed restrictions built into them as well.

Where SIDs and STARs are helpful

A few years back MMMX/Mexico City had some issues. It came down to the opening of the new MMSM/Felipe Ángeles (formerly Santa Lucia) airport nearby. When I say nearby, I mean literally just 40km away.

The arrivals and departures for each airport (combined with some terrain in the vicinity) sort of got in the way of each other a bit, causing big issues for the air traffic controllers who had to manage this. The idea of SIDs/STARs is that they accommodate flows and make ATC’s life easier, because they should provide a level of flow management in themselves.

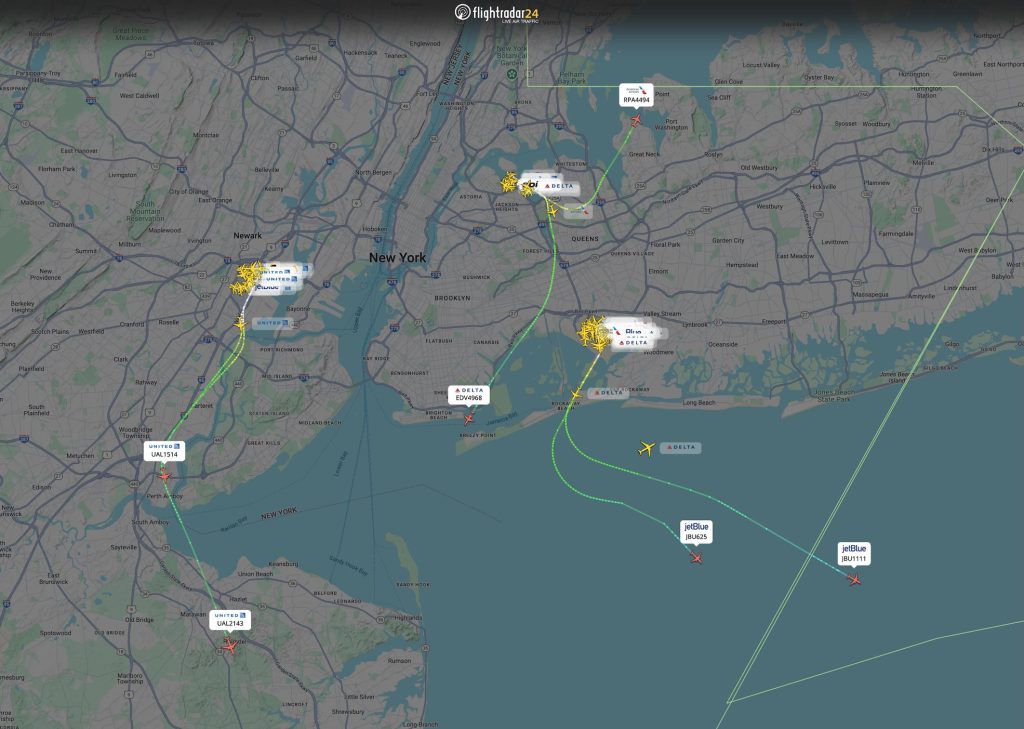

This isn’t the only spot where it can be a problem. New York airspace is some of the busiest in the world, mostly because there are loads of airports there. They offset some approaches to prevent issues with traffic heading into different airports, and ATC tend to bring aircraft down low and get them all lined up early to avoid conflict. All the SIDs and STARs have to consider all the traffic around the region so may have a holding pattern incorporated into them where ATC can “pile” aircraft up and provide separation when they’re too busy to efficiently feed directly onto approaches.

How do pilots fly the SIDs and STARs?

Well, first they tell their FMC (flight management computer) where they are and where they want to go, and they generally upload a company route which is sent to them automatically. Sometimes, if this isn’t working, they have to program the route bit by bit which is annoying and time consuming (they can select airways between waypoints so it doesn’t involve loading every single point thankfully). With the route in, they then check the airport’s ATIS to confirm the runway in use, and from this can work out which departure to expect, and they select this in their FMC as well.

One thing they have to manually dial up is the first stop altitude. This is the first upper limiting altitude. They will automatically level off at this unless ATC clear then to climb a higher level. This can be conveyed in several ways – “Climb Now, FLxxx” which means all other altitude restrictions are removed, or “Climb via the SID, FLxxx” which means they need to adhere to all altitude constraints on the SID (so not passing maximum altitudes until past the limiting waypoint).

To fly it, at least on the Boeing, they select LNAV and VNAV. What does this do? Well, it means once the autopilot is engaged, the aircraft is going to follow what is in the FMC – laterally (LNAV) and vertically (VNAV), and will also stick to the altitude and speed constraints too (also managed through the VNAV function).

It’s not all autopilot and go

Don’t go thinking pilots whack the autopilot in and job done. There are some “gotchas” with all this. First up – early, tight turns. If there are strong winds which are going to push the aircraft around in a big radius, then the pilots are going to need to help the aircraft out. This means ensuring a slow enough speed to make the tight turn, which may impact how early they can clean up and accelerate. This is mostly a noise thing.

They also have to think about terrain clearance. The aircraft will do its best to meet altitude restrictions, but the pilots might need to delay acceleration, select higher climb thrust settings etc to ensure it can do so. Let’s look at Gatwick again, this time the IMVUR 1Z off runway 08R (see above). Aircraft only have 4.7 miles to reach 2500 feet (that’s for noise), and have to not overshoot the KKN09 point – and with a strong wind, that 220 knots maximum speed might actually be too quick.

So even with all this technology assisting, pilots still need to ensure the aircraft can manage the departures they’re telling it to fly. Where there is significant terrain, like in KLAS/Las Vegas, pilots also have to check their aircraft can meet the SID climb gradients (or missed approach climb gradients on a go-around from an approach). On a very hot day with a heavy aircraft this could be an issue, same at some wintery spots where you find a combo of winter weather needing engine anti-ice (which reduces engine performance) and high mountains.

It’s all monitored

All of these paths are monitored, and if aircraft fail to fly them correctly the operators do get into trouble for it. A lot of airports publish reports ranking operators on their naughtiness (that isn’t exactly what they do). I used EGKK/London Gatwick as an example earlier because they publish particularly nice reports, and they are also the world’s busiest single runway so it’s a good one to look at.

What if there is no SID or STAR?

Smaller airports and less developed ones might not have SIDs and STARs. Before these (well, before RNAV and GPS became such a big thing), departures and arrivals were generally based off radio navigation aids – VORs, NDBs and DMEs. Some still are in fact, and even where there are RNAV based SIDs/STARs these might still be combined with conventional navaids.

Where there are no navaids available, or if the airport just doesn’t really need them, you may find pilots are vectored, or just have an “omni-directional” departure which sends them off in whichever direction…

Follow it all on Flightradar24

You can map the SIDs and STARs out by watching Flightradar24, especially when you enable the Aeronautical charts layers available in Settings.

If you want to follow through on individual charts too, then you can. NATS publish on the ones for UK airports online here. Go to part 3 – Aerodromes, AD2 and then click on whichever airport you want to look at and you’ll find links to the charts there. If you’re more of an FAA fan, then they have some available too.

Learn to brief like a pilot

Pilots brief their arrival and departure plan before heading in and out. This involves them confirming the name of the procedure and the effective date of the plate (the chart). They then “make a plan” – identifying obvious threats, talking about how to mitigate them, and discussing how they will fly the procedure.

So give it a go, download your own and try. Or just stick to watching aircraft zooming in and out of airports… but now you have more idea of how!

The post Flying SIDs and STARs: how traffic stays organized near busy airports appeared first on Flightradar24 Blog.