Pilots aspiring to fly professionally must first get “comfortable in the clouds.” We are *always IFR* and frequently in the clouds until minimums. So “step one” is lots of “actual” and this progresses over time to handling some pretty gnarly weather conditions. This article investigates the “edge of safety” – convective conditions with embedded tornadoes. Studying and learning about weather is a never-ending process, required effort if you want to stay safe. A lifetime of flying in different machines and conditions still provides new lessons daily (replay/reflect/redirect) but it also generates more questions. You can “build/buy hours” anywhere, but you only “gain experience” in real conditions. The key to safety is to always have a well-thought-out plan, a margin of safety, and a bullet-proof escape route if things change, (and they usually do).

A Severe T’Storm Warning is in effect for the Quad Cities until 2:45 p.m. as a storm with winds up to 60 miles per hour is moving North through the Quad Cities. The NWS has also issued a Tornado Watch for areas just barely SE of the Quad Cities.

For the date of May 20, the most precipitation ever recorded in Davenport, IA history is 3.50 inches which happened in 2025.

So, Where Do You “Draw the Line” for Safety?

The golden rule to staying safe is defining and maintaining a personal “margin of safety.” In commercial flying there are General Operating Manual (GOM) minimums and “Operations Specifications” (OpSpecs) which are approved exceptions to many rules. Then, of course, there is also the customer pressure to fly, which you very early have to learn to ignore completely for flight safety. Lots to ponder and parse for safe flight!

The commonly taught parameters to analyze aviation threats are: Pilot-Aircraft-enVironment-External conditions. There are the heart of any ACS flight test and also a very usable structure for safety. As pilots, we progress incrementally through graduated levels of challenges. Only as we gain skill and experience can we safely overcome greater challenges. Honest self-analysis is the most important (and difficult) meta-skill required to drive this risk-management engine. Excluding emotions from the analysis is difficult too.

The commonly taught parameters to analyze aviation threats are: Pilot-Aircraft-enVironment-External conditions. There are the heart of any ACS flight test and also a very usable structure for safety. As pilots, we progress incrementally through graduated levels of challenges. Only as we gain skill and experience can we safely overcome greater challenges. Honest self-analysis is the most important (and difficult) meta-skill required to drive this risk-management engine. Excluding emotions from the analysis is difficult too.

Ultimately, we always need to resolve the question, “Am I accurate and honest in this analysis of conditions vs skills?” For this reason, in tough conditions, I always solicit a second opinion. In many cases, step one is to wait for a “safe weather window!” Weather planning always involves the “3Ds of viable safety action:” Delay, Divert, Drive!“ A well-trained sport pilot can be safe in “very visual conditions!” Adding a private certificate and an IFR-rating (and currency) with experience in actual and “safe conditions” yeilds greater capability, but more complicated risk analysis. And the capability of the flying machine makes a huge difference. Growing up in a rural setting, we used to say: “Anyone can safely drive a slow tractor around a fifty-acre fenced-in field,” because everyone started operating heavy equipment at 12. We progress to where to are in the flight levels, navigating mature weather systems.

A well-trained sport pilot can be safe in “very visual conditions!” Adding a private certificate and an IFR-rating (and currency) with experience in actual and “safe conditions” yeilds greater capability, but more complicated risk analysis. And the capability of the flying machine makes a huge difference. Growing up in a rural setting, we used to say: “Anyone can safely drive a slow tractor around a fifty-acre fenced-in field,” because everyone started operating heavy equipment at 12. We progress to where to are in the flight levels, navigating mature weather systems.

Professional pilots – potentially ATP-rated co-captains flying a highly capable jet – can safely navigate CAT II landing and very challenging enroute conditions safely. These same conditions would be unsafe or unwise for less skilled or experienced pilots flying more basic equipment.

I wrote another blog years ago on safely negotiating convective activity (that created some murmuring among the “safety yenta“) but remember, this was two highly-experienced pilots flying in a well-equipped jet.

If I were flying my Cherokee Six yesterday, this trip would be a clear “no-go.” The capability of the machine is a huge factor in any aviation decision-making process. A jet can top most convective activity en route. But it has unique safety concerns like safety on the ground (a necessary hangar) and the requirement for a return flight later. This adds built-in safety pressure to get everyone home: the “mission mentality” has to be managed carefully.

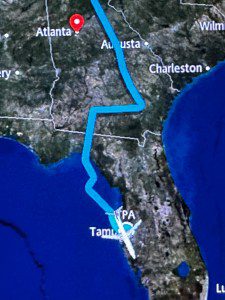

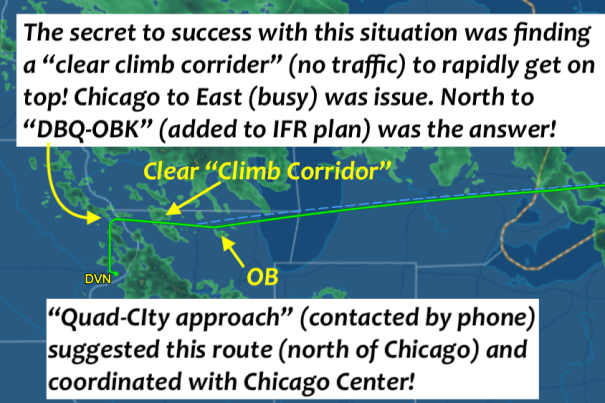

When you are single-pilot, “teamwork” means studying weather and airspace carefully and using the local professionals you have at your disposal (see Hobie’s SRM blog). Departure at the end of this day was definitely nasty requiring some delay and initially looked unworkable (the jet was in a hangar and the TSMs were rolling through). But once the biggest nasty stuff moved east – and it was clear to the west – a workable strategy finally developed. The plan was to climb in the clear, then turn east and top the storms (which were diminishing at this point). The question was how to make this climb possible with local IFR at the departure (KDVN – non-tower) and busy Chicago to the east?

A call to the local (Quad-city) departure radar (use your local resources) provided a solid plan based on comprehensive local knowledge. Initially fly straight north clear of convective to DBQ. This got me north of a lot of the weather and also Chicago traffic at ORD and MDW (this would have prevented an unrestricted climb). This ensured a “clear climb corridor” east to Northbrook VOR (OBK). This routing was added to the IFR plan and assured the ability to get up and over the convective. When you are consulting with ATC they will almost never state a specific plan due to liability, but the information is there for the savvy pilot. Plan B was obviously to bug out to the clear area west of KDVN.

The last sticking point with my self-assessment of this plan was this ominous statement: “We do not know the actual tops because no one else is flying.” This sounded scary to me. A good pilot must always maintain their humility and ask the most important question: “Am I doing something dumb or unsafe here?” (one reason crewed flight is 7X safer than SP) See “Combat Advice”

Call an experienced and trusted pilot friend!

With tough weather decisions, always seek the independent counsel of a seasoned second opinion. I personally maintain a list of trusted senior pilots whom I can call and check my planning!” This is what we do in a crewed situation. “Am I thinking straight here?” and “What would be *your* plan for this operation?” Combine this feedback with a sure-fire “Plan B.” With serious convective conditions, that always requires an absolutely solid escape route (in this case head west).

With tough weather decisions, always seek the independent counsel of a seasoned second opinion. I personally maintain a list of trusted senior pilots whom I can call and check my planning!” This is what we do in a crewed situation. “Am I thinking straight here?” and “What would be *your* plan for this operation?” Combine this feedback with a sure-fire “Plan B.” With serious convective conditions, that always requires an absolutely solid escape route (in this case head west).

It all worked out so well, the passengers never felt a bump. They mentioned how smooth is was after my instructions to “keep the belts tight and no beverages on departure.” They probably figured any schlump could fly on a day like this (never make that error in judgment). I’d rather be “chicken little,” than Icarus.

It all worked out so well, the passengers never felt a bump. They mentioned how smooth is was after my instructions to “keep the belts tight and no beverages on departure.” They probably figured any schlump could fly on a day like this (never make that error in judgment). I’d rather be “chicken little,” than Icarus.

As I write this, all the weather I flew over yesterday rains down on me once again; retribution! Always *reflect* on your flying experiences. Fly safely out there (and often)!

As I write this, all the weather I flew over yesterday rains down on me once again; retribution! Always *reflect* on your flying experiences. Fly safely out there (and often)!

Flight test anxiety is one of the most common obstacles to success during an FAA evaluation. It occurs at every level, from initial PPL to jet type ratings! This webinar will offer solutions based on scientific techniques to quiet those test-day butterflies and ensure a better experience. A calm, confident applicant presents their best performance on flight test day!

Flight test anxiety is one of the most common obstacles to success during an FAA evaluation. It occurs at every level, from initial PPL to jet type ratings! This webinar will offer solutions based on scientific techniques to quiet those test-day butterflies and ensure a better experience. A calm, confident applicant presents their best performance on flight test day!